Dispelling the Illusion of Dividend Capture Strategies

Why Dividend Capture Fails - No Matter How Clever the Trade

An Idea That Feels Like It Should Work

Dividend capture is one of those ideas that refuses to go away - not because it is mysterious or complex, but because it feels obvious.

The logic is simple and appealing:

- Buy a stock before the ex-dividend date

- Hold it long enough to receive the dividend

- Sell it shortly afterward

- Repeat

It feels like getting paid for timing or insight.

When investors discover that the basic version doesn’t quite work, they often refine it:

- Hold the stock for just the “right” window

- Use margin to amplify the dividend

- Add covered calls or protective puts

- Try the trade from the opposite direction

What’s striking is not that these variations fail - it’s how consistently they fail.

This article walks through why, using one simple numerical example throughout. No pricing models. No calculus. Just arithmetic, accounting, and market mechanics.

I. What Actually Happens on the Ex-Dividend Date

Let’s begin with a clean, neutral setup:

- Stock price the day before the ex-dividend date: $100

- Declared dividend: $1.00

- No taxes, commissions, or borrow costs

- No assumptions about market psychology

When a dividend is declared, it is a known cash payment. That cash will leave the company’s balance sheet and be paid to shareholders of record.

Because the cash payment is known in advance, prices adjust to reflect it before it happens.

On the ex-dividend date:

- The stock opens lower by approximately the dividend amount

- Options, forwards, and synthetic positions adjust at essentially the same moment

- The value doesn’t disappear - it moves

This is not a belief about market efficiency.

It is not a theory about trader behavior.

It is bookkeeping.

Only the most advanced institutional participants - operating at extremely high speed, with privileged execution and scale - can somewhat consistently arbitrage the tiny, fleeting mismatches that exist during that adjustment. For everyone else, the adjustment happens all at once.

With that in mind, let’s what’s been tried for dividend capture.

II. Why Timing the Holding of Stock Doesn’t Create Opportunity

The classic dividend capture trade

- Buy 100 shares at $100 → $10,000

- Ex-dividend date arrives

- Stock opens at $99

- You are owed a $100 dividend

Your position now looks like this:

- Shares worth $9,900

- Dividend receivable of $100

Total value: $10,000

You didn’t lose money - but you didn’t gain any either.

You received cash, and the market reduced the share price by the same amount.

Adding leverage doesn’t help

Suppose you use 2:1 margin:

- Buy 200 shares at $100 → $20,000 position

- Borrow $10,000

On the ex-dividend date:

- Shares fall to $99 → $19,800

- Dividend received: $200

$19,800 + $200 = $20,000

Minus borrowed funds → same equity as before

Leverage magnifies both sides of the equation equally. Nothing about your returns changes. In fact, the borrowing cost of margin works against your earning power.

III. Why Elaborate Derivatives Don’t Change the Outcome

When holding the stock alone doesn’t work, investors could turn to stock options.

Covered calls

- Buy 100 shares at $100

- Sell a call

Because the dividend is known, call prices are already reduced to reflect it. The call premium incorporates the expected price drop.

On the ex-dividend date:

- The stock drops by $1

- You receive the dividend

- The call premium you collected was already lower by that same $1

The components move, but the net result does not.

Buying calls instead

If selling calls doesn’t work, maybe buying them does?

But calls lose value on the ex-dividend date for the same reason: the underlying stock price drops.

- Buy a call

- Ex-date arrives

- The call loses roughly the dividend amount

Again, no net advantage.

Buying puts

Puts increase in value as the stock price falls - but put prices are already higher before the ex-date because that fall is expected.

The gain is prepaid.

Options don’t create opportunity here because they inherit the same adjustment as the stock itself.

IV. Why Taking the Opposing Position Doesn’t Deliver

At some point, a thoughtful investor asks the most reasonable question of all:

“If owning the stock before the dividend doesn’t work, shouldn’t shorting it work instead?”

Let’s see.

Shorting the stock

- Short 100 shares at $100 → receive $10,000

- Stock drops to $99 on ex-date

- Buy back at $9,900 → $100 gain

But short sellers must pay the dividend to the lender.

$100 gain − $100 dividend owed = $0

Synthetic shorts and other reversals

Synthetic positions - long puts combined with short calls - behave exactly like real shorts.

They gain from the price drop and lose the dividend value simultaneously.

Changing direction doesn’t help, because the cash obligation follows the position.

There is nowhere to stand where the arithmetic changes.

V. This Isn’t Market Efficiency - It’s Bookkeeping

It’s tempting to explain all of this by saying “markets are efficient.”. But that’s really giving too much credit to market participants.

Dividends behave like:

- stock splits

- bond coupon payments

- futures roll adjustments

These are not trading opportunities. They are mechanical value transfers. You can cut a whole pizza all kinds of ways, but in the end its the same pizza.

When the cash flow is known in advance, prices adjust to reflect it. Stocks, options, and derivatives all move together at essentially the same moment.

This doesn’t mean prices are perfectly flat around ex-dividend dates. Event studies consistently show small run-ups into the ex-date and reversals afterward, driven largely by investors chasing the dividend. But these patterns are unstable, capacity-constrained, and disappear once real-world frictions are applied — leaving no dependable edge for typical investors.

This is why dividend capture doesn’t fail occasionally - it fails universally. Perhaps it’s more appropriate to say that there isn’t an edge to capture. Mr Market and the accounting processes work fast to keep balance.

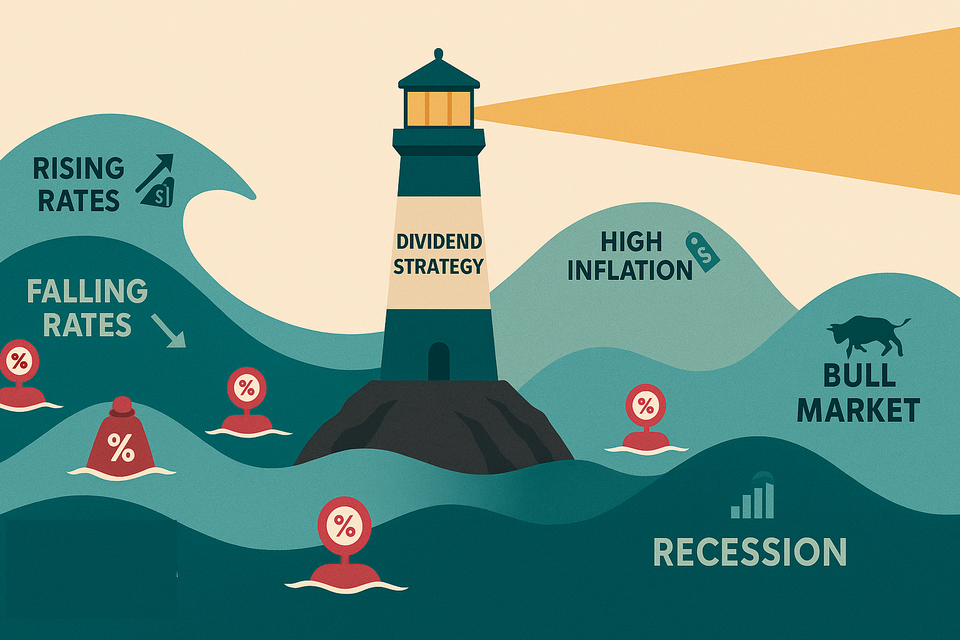

VI. What Dividends Are Actually Good For

Dividends are not tricks to be captured. They are tools for long-term investors.

They provide:

- cash flow

- discipline around capital allocation

- a way to shape return composition over time

Dividends matter when they are owned repeatedly, reinvested thoughtfully, and integrated into a broader portfolio plan.

They do not create value at a moment in time - they distribute value over time.

Understanding this frees investors from chasing narrow tactics and redirects attention toward durable outcomes.

The Value of Letting the Illusion Go

Dividend capture strategies persist because they feel intuitive. But once you understand what actually happens - once you see how prices, options, and obligations adjust together - the illusion loses its hold.

That understanding is not limiting. It’s liberating.

It allows investors to stop trying to out-arbitrage accounting mechanics and instead focus on what dividends genuinely offer: consistency, planning, and long-term participation in cash-generating businesses.

Dividends reward ownership, not cleverness. And once that distinction is clear, better investment decisions tend to follow.